German Technical Innovation in Late 19th Century Firearms Design: The First Practical Semi-Automatics

The late 19th century, at the close of what we call the “Industrial Revolution”, saw a flurry of technical innovations spurred not only by engineering advances, but also by the discovery of new chemical processes which allowed for previously unimaginable designs. And so we saw the refinement of petroleum (literally “stone oil”) into a light, extremely flammable substance (gasoline) which allowed for the construction of relatively light engines, with extreme power. Without this advance, for example, the Wright brothers would not have been able to power their first aircraft. Equally, the development of smokeless gun powder (nitrocellulose and cordite) as a propellant in firearms allowed for the development of semi-automatic handguns. Previous to this, black powder fouling made the movement of internal parts impossible with repeated use. In the fore of this development were the German engineers Hugo Borchardt, Alois Schmeisser, Georg Luger, and the brothers Paul and Wilhelm Mauser.

Military commanders have always sought ways to improve firepower of the infantry, the most important arm of any army. While artillery, cavalry, navy and (today) air force units may be able to clear the way for the infantry, it is the ground troops which must eventually occupy and subjugate the enemy in order to control the field. Therefore, infantry armaments have always been the most important subject of research and improvement. During the 19th century, we have seen the advancement from single-shot flintlock pistols and muskets to faster loading percussion guns, multi-shot revolvers, long-range rifles, and finally cartridge guns. This final development was the height of firearms technology at the beginning of the 1890’s. Handguns and rifles were still charged with black powder as a propellant, with all its shortcomings: black powder is a messy, sooty affair as anyone who has shot a black powder gun can attest to. Firearms design of that period shows how the engineers attempted to allow for this problem. Colt only ever made one black powder percussion revolver with a solid frame (the 1855 Root) due to the problem of fouling between the cylinder and frame.

The “Root” was not a military sidearm, and therefore repeated use in battle was not an issue. Remington modified their army and navy revolvers several times in order to mitigate the fouling problems – they incorporated cut-outs at the bottom of the frame, for example, and reduced the barrel lugs, exposing the barrel threads in order to minimize the contact area between the front of the cylinder and the barrel.

Colt M1860 Army: Note the open space in front of the cylinder, and open-top design. Both are meant to reduce binding of the mechanism due to black powder fouling

Remington New Model Army: note the exposed barrel threads at the front of the cylinder

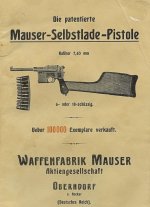

This was thought to be the “status quo” from the 1850’s until the early 1890’s. It was the invention of cordite, a mixture of nitroglycerine and nitrocellulose, by British chemist Sir James Dewar and Sir Frederick Abel in 1889 which would change the course of military firearms development. Not only was this new propellant more powerful than equal amounts of black powder, it was also virtually smokeless and caused no fouling of the mechanism. This allowed designers to incorporate delicate internal parts which eventually turned the conventional revolver into a truly semi-automatic handgun. The earliest of these were the Borchardt “Construction 93” (C-93), the Bergmann Model 1893, and the Mauser “Construction 96” (C-96). The one characteristic all of the early semi-automatics had in common was the “delayed blow-back” operation of the action: the receiver / slide is opened by gas pressure, resisted against by the mass of the receiver, and spring tension. This simple method is still used today in some low-cost, small caliber semi-automatic handguns. The three guns, the Bergmann (System Schmeisser), the Borchardt, and the Mauser, all competed for military acceptance at the same time. While all of them had their proponents as well as their critics, only the Mauser eventually achieved acceptance by ordnance departments around the world.

Even after the release of the famous Luger pistol in 1900, Mauser’s C-96 (and many copies) would continue to be carried by military and police units until the 1950’s. The other two, Bergmann and Borchardt, faded into obscurity. Borchardt’s design would be the basis for Luger’s pistol, while Schmeisser/Bergmann attempted to modify and improve their pistol over the years. In the end, they could not compete with the Luger and Mauser semi-automatic pistols. The last Borchardt was made in 1902, and the last of the Bergmann in 1897. Borchardt refused to modify his design despite widespread criticism, while Bergmann continued to experiment with the Model of 1896, 1897, Bergmann-Simplex, Bergmann-Mars and Bergmann-Bayard.

For today’s collectors, all three are iconic examples of early semi-automatic handguns. The most common is the Mauser C-96 and its many copies, all made in the hundreds of thousands. For Canadian collectors, as of this writing, only those C-96’s with serial numbers below about 4000 would be acceptable as an antique (and even this is tenuous, as the RCMP have their own interpretation of this). The Mauser archive lists guns in the 2000’s and 4000’s having been sold by John Rigby & Co. in England in February and March of 1898. Both the Borchardt and Bergmann pistols are considered antiques, as they were discontinued before 1898. A decent quality, antique Mauser will fetch upwards of $9,000, while a Borchardt will be easily in the $25,000 to $40,000 range. A Fine Bergmann will sell in Canada for between $6,000 and $10,000.