Ah, I

am very snobbish on British guns.

“Guilty!, Guilty!” I must plead…

I also think no one beats the French for wine, and the only cars that make my blood fizz are Italian. To each their preferences, I guess, in this wonderful world. As to whether British guns are overly expensive, that is for markets to decide. Second-hand, they can be the bargain of a lifetime, and a lifetime’s worth of joy and pride.

The recent examples by Churchill presented in this thread, and comments on apprenticeships, prompted my brain cells to reflect further on the incredibly intertwined nature and histories of the British gun trade through apprenticeships, and the evolution of trade names.

The typical formation of a gunmaker started with an apprenticeship under a recognized master gunmaker. In time, the apprentice would become a gunmaker, possibly be taken on as a partner, or move on to set up on their own. In this way, the pedigree of most gunmaking names can be traced back to the Mantons or other famous 18th-century or early 19th-century gunmakers. There were notable exceptions, the tobacconist Harris Holland being one, and another being Benjamin Cogswell, the pawnbroker.

In my earlier posts, should anyone decide to scroll back, I described how many gunmaking firms can be traced back to apprenticeships under Joseph Manton, including Boss, Purdey, Moore, Lancaster, Fuller, Lang, Greener (Senior), and so on. The better one’s business became, the more consequential apprenticeships in these firms were in terms of future success and recognition, or the more solidly the firms became by keeping evolving businesses within the family line (this latter point is not only limited to British gunmaking, as the Italian firm of Beretta has been kept in the same family for the past 499 years). In some firms, adding “& Son” marked the addition of a family member after completing their apprenticeship, or made a full partner, as in the case of Holland & Holland. Some used their origins as part of their identity -- when James Purdey started out marking his guns with his name, he added “From Manton,” and the London gunmaker William Evans, who learned his trade under James Purdey and Harris Holland, marked his guns “From Purdey's.” Today, the cheapest new William Evans sidelock double, built for them by Grulla-Armas, S.L. of northern Spain, can be had for a mere $22K, though if you want the one based on the H&H design, maybe with a round body, that will set you back more than $36K; hand work is not cheap, regardless of country of origin. Oh, and if you want a sporting clays-ready over/under, William Evans has one too, also Spanish-made but designed by Perazzi, but price is on application only.

(All of a sudden, a fine used British double on the Canadian market for $1-2K, or less, seems like a sweet deal!) Sorry, I digress.

As I mentioned, there have been a small number of self-taught gunmakers, persons with an affinity towards guns and shooting, and who were inventive and skilled with tools, but these self-taught makers were the exception. In any case, they might have been more concerned with the business side of things, rather than the actual making of guns or gun parts. Guns were generally built of parts made by specialist craftsmen, and assembled and finished by different specialists. These skills had to be learned, and this was usually done through apprenticeships. A typical apprenticeship to learn a trade was for seven years, though in some cases could be longer. Such apprenticeships were bought and paid in advance, a welcome source of money for the master. Pay was minimal and might only be in the latter years of the training, a sum less than that for a journeyman (daily paid worker, derived from the French

journée) [Note: in gunmaking a journeyman was a craftsman who although had completed an apprenticeship, could not employ other workers; they were often called jack or knave, and this is where the expression

“jack of all trades master of none” comes from]. Masters would be obliged to provide room and board, which is why so many gunmakers had an apprentice living with them at their work address. A typical age to start an apprenticeship was 14, but could be younger depending on the trade. During the 7-year period, the apprentice could not gamble, or go to the theatre or a public house (bar), and certainly could not marry. Some kept apprenticeships very much in the family, and in the gunmaking business, this meant training sons who were expected to learn and continue the business. There were other incentives for completing the apprenticeship, for instance an apprentice who had not completed his term would not legally be able to work in his trade for another master.

The first years would involve tedious, repetitive work until a sufficient level of skill was achieved. An apprentice would not be let anywhere near finished parts or a complete gun, lest he make a mistake that would require parts being discarded or work re-done. An apprentice would typically start by making the tools they would be using throughout their working lives. After completing an apprenticeship, the worker would usually continue as a journeyman for four or five years or more. They could then become a Master in their own right by applying to the Guild (The Worshipful Company of Gunmakers, a livery company of the City of London established by Royal Charter in 1637), a process involving a fee and the presentation of a "masterpiece” to be judged by the Guild (now you know where the word

“masterpiece” came from). The interlinkage of master and apprentice, and apprentices becoming masters, means that the educational lineage of gunmakers can be traced through the apprenticeships they went through, and the apprentices they in turn trained. Here is a Harris Holland 12-bore, from the time when his nephew was his apprentice; he might have allowed his nephew to make the screws:

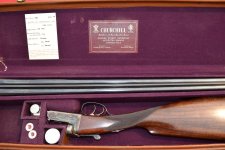

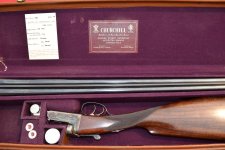

As to the Churchill name, and the rights to using it, that’s another story. At the age of 14 in 1870, Edwin John Churchill was apprenticed to the gunmaker William Jeffery of Dorchester. He then moved to London and in 1877 worked for Frederick Thomas Baker, becoming its manager by 1882. In 1891, EJ Churchill left to establish his own business. He was also an accomplished live-pigeon shooter by this time, known nationally and internationally for his shooting skill and his ability as an instructor and gun fitter. Churchill used outworkers to produce gun parts and complete guns to his preferred designs. He also recruited his own skilled staff, but like so many firms, still relied heavily on outworker talent, and the addition of family members. In 1893, his son Henry joined as an apprentice. In 1899, his nephew Robert joined the firm, beginning his apprenticeship at the age of 14 in 1901. Business boomed, and by 1905, EJ Churchill was appointed gunmaker to the King of Spain, Alfonso XIII. Not all was quiet at home; EJ’s wife died in 1904 from a drink-related illness, perhaps exacerbated by EJ’s dalliance with a Miss Houssart, with whom he fathered three children. They did eventually marry, but secretly (most of EJ’s family was not aware). In 1906, at the age of 12, James Chewter began working for the firm; he was rumoured to be another illegitimate son, who later became the company's general manager and stayed with the firm until 1962. Ah, when guns were made by people, not faceless companies!

EJ died in 1910, and Robert continued the business. In 1913 he started his “Hercules” boxlock ejector, and by 1920 the “Hercules” model had the scroll back action, as seen in Sillymike’s picture. EJ had made short-barrelled guns, but it was Robert who became closely associated with 25-inch barrels more than any other maker, because of his live pigeon shooting success and because he developed a style of shooting to suit short barrelled guns. His book,

How to Shoot, was published in 1925 and revised several times. In 1917, the firm became E J Churchill (Gunmakers) Ltd. In 1933, the firm received a royal warrant from the Prince of Wales, though this appointment changed in 1936 when George V died and Edward VIII abdicated in 1937. In 1955, Robert wrote his second book,

Game Shooting; it is a great read, and I highly recommend it. Robert died in 1958. In 1959, the firm was sold to Interarmco (UK) Ltd, who also owned Cogswell & Harrison, and the name changed to Churchill (Gunmakers) Ltd. In 1963, the firm merged with Atkin Grant & Lang Ltd, though each firm kept their name to conduct business. In 1971, Churchill (Gunmakers) Ltd changed its name to Churchill, Atkin Grant & Lang Ltd. In 1972, the firm was bought by a large company, Thomas Poole & Gladstone China Clay Ltd. It was sold again in 1973 to the Harris & Sheldon Group. In 1977, that company decided to stop gunmaking activities, and Churchill staff started a workers’ co-operative, selling guns under the name Churchill (Gun Works) Ltd; it ceased trading in 1980. In 1981, a former production director bought the plant, machinery, and tools and registered a new company, Masters Gunmakers (from Churchill) Ltd. In 1993, the name was changed again, to E J Churchill (Gunmakers) Ltd. However, plans to build guns again never materialized.

OK, this has been a particularly long-winded, convoluted, and overly detailed history of a name that has nothing to do with the Turkish gunmaker Akkar, which obtained a registered trademark for the brand name “Churchill” in Turkiye in 2013. Akkar must have figured they could capitalize on using a recognizable name from the gun world, but there is no connection whatsoever to the storied Churchill name and its gunmaking heritage.