You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Quenching cast bullets

- Thread starter y2k

- Start date

unstableryan

CGN Ultra frequent flyer

- Location

- Beautiful Okanagan Valley

I don’t know for sure, but I water drop all my cast. This is what I got from grok. Looks like if antimony is decently present, it bumps it up a bit. I do it because I tried dropping onto cloth or something and sometimes a base deforms and I like casting as fast as it makes good bullets.

Attachments

saskgunowner101

CGN Ultra frequent flyer

- Location

- near Prince Albert

Do water quenched bullets retain their hardness for extended periods of time though? I recall reading that it wasn't a permanent change, that eventually they return to the original hardness.

no they don'tDo water quenched bullets retain their hardness for extended periods of time though? I recall reading that it wasn't a permanent change, that eventually they return to the original hardness.

I just tested some bullets I cast 10 years ago and they lost about 5bhn

BattleRife

CGN Ultra frequent flyer

- Location

- of No Fixed Address

One potential advantage is in uniformity. I used to drop my bullets onto a damp towel, but it's rather obvious that the side that touches the towel cools faster than the side that does not. Also the spots that touch the towel often take on a texture of the thread pattern, while the other side remains smooth, I didn't like that, either.

So now I usually water drop. Appearance is definitely more uniform, and I assume the cooling rate is, as well. I do it mostly to get the uniform appearance, if there is a functional difference I have never noticed it.

Answers about hardness should come with a big asterisk. Lead alloys don't quench harden, but they will precipitation harden. Precipitation hardening has 3 distinct steps:

- Select alloying elements dissolve into the lead at high temperature

- Rapid quenching traps the alloying elements in the dissolved state (not a natural or stable condition, as thermodynamically they should occur as independent phases within the lead matrix)

- With time, the elements precipitate out of solution to form millions of tiny islands in the lead. It is these islands that increase the strength and hardness of the material.

The problem occurs at step 1. Much of the time when casting, we aren't opening the mould until the temperature has dropped below the dissolution temperature, so some or all of the alloying elements have already come out of solution to form independent phases before the quench happens, instead of trapping the necessary elements in a dissolved state. Or, due to variations in casting technique maybe sometimes you trap the elements in solution, sometimes you don't, with resultant variability in how much hardening can happen.

This is why it is more effective to reheat the bullets in a separate step, hold for a few minutes to ensure dissolution, then quench.

So now I usually water drop. Appearance is definitely more uniform, and I assume the cooling rate is, as well. I do it mostly to get the uniform appearance, if there is a functional difference I have never noticed it.

Answers about hardness should come with a big asterisk. Lead alloys don't quench harden, but they will precipitation harden. Precipitation hardening has 3 distinct steps:

- Select alloying elements dissolve into the lead at high temperature

- Rapid quenching traps the alloying elements in the dissolved state (not a natural or stable condition, as thermodynamically they should occur as independent phases within the lead matrix)

- With time, the elements precipitate out of solution to form millions of tiny islands in the lead. It is these islands that increase the strength and hardness of the material.

The problem occurs at step 1. Much of the time when casting, we aren't opening the mould until the temperature has dropped below the dissolution temperature, so some or all of the alloying elements have already come out of solution to form independent phases before the quench happens, instead of trapping the necessary elements in a dissolved state. Or, due to variations in casting technique maybe sometimes you trap the elements in solution, sometimes you don't, with resultant variability in how much hardening can happen.

This is why it is more effective to reheat the bullets in a separate step, hold for a few minutes to ensure dissolution, then quench.

I tried water dropping and I couldn't see any advantage. Kind of a pain because extra step drying your bullets.

I use a fluffy probably cotton bath towel to drop my bullets on. I don't get dents or deformity. I'm basically shooting straight lead.

Speed kills accuracy for me. Black powder velocities or less works the best for me. If I want more range or better wind buck. I use a heavier bullet.

I've never messed with powder coats. Don't see the need.

Sometimes with old guns the softer lead bullets will shoot more accurate than hard wheelweight bullets .

But I've never had hard bullets outshoot the softer bullets.

I use a fluffy probably cotton bath towel to drop my bullets on. I don't get dents or deformity. I'm basically shooting straight lead.

Speed kills accuracy for me. Black powder velocities or less works the best for me. If I want more range or better wind buck. I use a heavier bullet.

I've never messed with powder coats. Don't see the need.

Sometimes with old guns the softer lead bullets will shoot more accurate than hard wheelweight bullets .

But I've never had hard bullets outshoot the softer bullets.

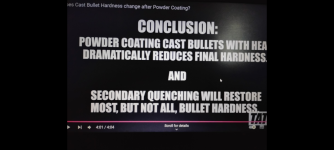

go to castboolits and find the answer you seek. personally, I quench my bullets coming out of a powdercoat treatment but I really can't say I have proof it works because powdercoat seems to cover up a lot of alloy issues. I still get some minor leading and what appears to be some kind of epoxy residue coating in the bore. it cleans up very quickly but I do experience a bit of accuracy degradation at the range.

>grokI don’t know for sure, but I water drop all my cast. This is what I got from grok. Looks like if antimony is decently present, it bumps it up a bit. I do it because I tried dropping onto cloth or something and sometimes a base deforms and I like casting as fast as it makes good bullets.

which alloy at what velocity? Have never had leading with PC'ed at slow speedspowdercoat seems to cover up a lot of alloy issues. I still get some minor leading and what appears to be some kind of epoxy residue coating in the bore. it cleans up very quickly but I do experience a bit of accuracy degradation at the range.

I use wheel weights to cast bullets and the lead that comes out of there or whatever exactly it all is I don’t know what alloys are in that stuff. It’s hard enough that I can’t make a imprint with my thumbnail like you can with soft point jacketed 4570 or 357 magnum etc..

wheelweight alloy/extra tin @1050 fps. seems to me the tapered ramp of the rifling might be the culprit. it is quite abrupt which could be tearing the powdercoat. did a few smash tests with a hammer and the powdercoat did not show any flaking or separation from the bullet. leading shows right at the leade/throat in a semi auto pistol barrel fairly quickly (25-30 rounds) then stays at a constant level over the next couple hundred rounds. not hard to remove the powdercoat residue but it takes a bit of scrubbing to completely remove the lead.which alloy at what velocity? Have never had leading with PC'ed at slow speeds

and reduces to zero at the muzzle.

BattleRife

CGN Ultra frequent flyer

- Location

- of No Fixed Address

That Youtube video is a good start, but a person who really wanted to get control of hardness would need to do some more work.

As I tried to outline in my post #7, the key variable (beyond making sure you have a hardenable alloy to start with) is temperature. How hot is the bullet when it hits the quench water? Most powder coatings call out 375°F as the minimum baking temperature, but you can go hotter to shorten the curing time. A temperature of 375F may just soften the bullet no matter how you cool. Go 100 degrees hotter, and maybe then you can fully recover or even gain over the as-cast hardness.

As I tried to outline in my post #7, the key variable (beyond making sure you have a hardenable alloy to start with) is temperature. How hot is the bullet when it hits the quench water? Most powder coatings call out 375°F as the minimum baking temperature, but you can go hotter to shorten the curing time. A temperature of 375F may just soften the bullet no matter how you cool. Go 100 degrees hotter, and maybe then you can fully recover or even gain over the as-cast hardness.