- Location

- Northeastern Ontario

This is the first post of what will probably be several about this topic. I don't know how they will lay out in the forum.

It will likely require editing and very possibly correction. Any mistakes are mine.

Finding Good Ammo and Why it’s Hard to Find

I continue to learn about shooting .22LR all the time. It’s never ending. Not too long ago I only used .22's casually for hunting and plinking and didn’t give any thought to shooting seriously for accuracy and precision. Now shooting them has become almost an obsession. I shoot from the bench with a front rest and rear bag. I don’t compete. I shoot to try to get the smallest groups possible. I shoot targets of five groups of five shots each or ten groups of five shots. No one else at my range shoots .22LR seriously. Perhaps it’s fortunate that my shooting season is not year round, as my range is accessible only when there is no snow on the ground. There are other things in life besides shooting. More practically I can’t afford to shoot more than a few cases of ammo a year.

Looking back at when I began to learn about shooting .22LR for accuracy and precision – that is, the smallest groups where I wanted them – there are a few things I wish I would have known back then. This is not intended for experienced shooters who have already learned many lessons about .22 rimfire. This is for the neophyte I was not so long ago, some things I know now that I wish I knew back then.

This is about what I learned in general about finding good ammo or understanding why it’s hard to find. It presupposes that the rifle is capable of very good accuracy and precision and that the shooter understands the basics about shooting from the bench. If the rifle is up to the task, getting the most out of it is up to the shooter and the ammo.

It can be a complicated and perplexing mix. Even when assuming consistently good shooting, sometimes a rifle may throw fliers with the best ammo from time to time. But no matter how sound the shooter and rifle might be, the best ammo can’t always be expected to be free of defects or flaws that result in errant shots. It is impossible to avoid altogether. Sometimes rimfire shooting challenges explanation

What have I learned? – A short summary

Often more expensive ammo shoots better than more modestly priced ammo. But it’s not always the case. Ammo quality varies by lot. Most lots are average for that grade of ammo, but some are better and some are worse. The particular lot you have can make a difference between good results and not so good. The same ammo doesn’t necessarily shoot the same with different rifles. Different individual rifles of the same make and model don’t necessarily shoot the same ammo with the same results. The wind can affect results downrange more than many shooters might think.

Finding the best ammo is not easy. When there are errant shots – that is, those that stray from an otherwise good group – they can be caused by one of several things: the wind (if it’s there), the ammo, the rifle, or the shooter or how he sets up his rifle on the bench, a judgment of the shooter nonetheless. The human factor is real especially with shooters who are still learning, working on their technique – but it’s hard to quantify and, I find, harder still to describe.

Finding the ammo your rifle “likes”?

When I began to read about .22 rimfire accuracy, one of the first things I learned was to use standard velocity ammo because it is usually more accurate than high velocity ammo. That was true then and will continue to be true.

I also thought I learned that it was very important to “find the ammo your rifle likes”. By testing a variety of ammos it was supposed to be possible to find the kind that shot most accurately. There is some truth in that kind of advice but there is something misleading in it too. It’s not the same as sampling different flavours of ice cream and picking the one you like. You can say you like chocolate, but not all chocolate ice cream tastes the same.

If testing a number of different ammos, it is possible to identify one of them as producing better results than the others. This is the easy part.

Is it as easy as that? Not really.

It might be tempting to suggest that all that testing should show that the more expensive ammo should produce the best results. That would be a convenient “short cut” and it might happen. The best results, however, might come from ammo other than the most expensive. We simply can’t know in advance. Why? There are several factors at play here and they affect every variety of ammo.

While every rifle may shoot the same ammo differently, perhaps the biggest variable is the ammo itself. Different brands of ammo have unique characteristics. They can have differences in casings, primer material, and propellant – including bullet composition and sometimes shape. Even when it has the same name on it, it doesn’t necessarily shoot the same. To a greater or lesser degree, each variety of ammo has unique characteristics with the result that they respond differently in different rifle barrels. We usually can’t discern these differences by looking at the ammo. The differences, however, are revealed in their own way on the targets.

Lot variation.

Ammo is made in batches called lots. The ammo in each lot should be very similar. But some lots have more consistency between individual boxes or rounds than others. While most lots are generally close to each other in terms of accuracy results, there are differences that can make two different lots of the same ammo seem as different as night and day. A lot of ammo that shoots well in one rifle may not shoot nearly as well in another. That is because each rifle is unique to a degree. Two rifles of the same make and model may not shoot the same lot of ammo with the same results.

To illustrate I’ve shot some lots of Center X that has produced very good results with one of my Anschutz rifles. At the same time I’ve shot other lots of Center X with the very same rifles and the results are consistently inconsistent, so much so that the results are embarrassing in comparison. While most lots of a given brand are relatively close to one another in terms of results, sometimes the differences can be significant.

Is every variety of ammo populated by inconsistent lots? I think there is a good chance that all varieties of ammo have inconsistent shooting lots. I’ve shot some lots of SK Standard Plus and SK Rifle Match that have produced better results than some lots of Center X. I’ve had some lots of Midas Plus shoot very well indeed, while others are poor enough to not justify the cost of $200 per brick (500 rounds). While it is often more accurate, the price tag of the match ammo is not a guarantee that it will shoot well in your particular rifle or even better than less expensive fare.

To illustrate the potential difference between one lot and another -- and, incidentally, to show how different barrels can produce different results with the same ammo -- consider these results from the Eley Lot analyser, which shows, for what they're worth, Eley test results for their various ammo products, according to lot number.

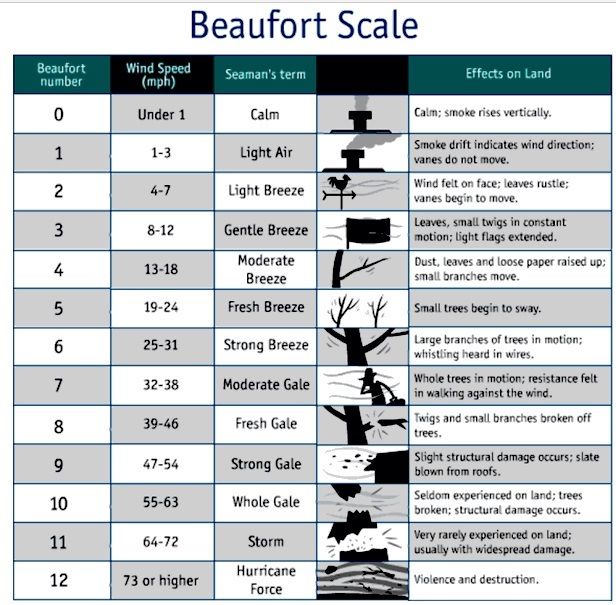

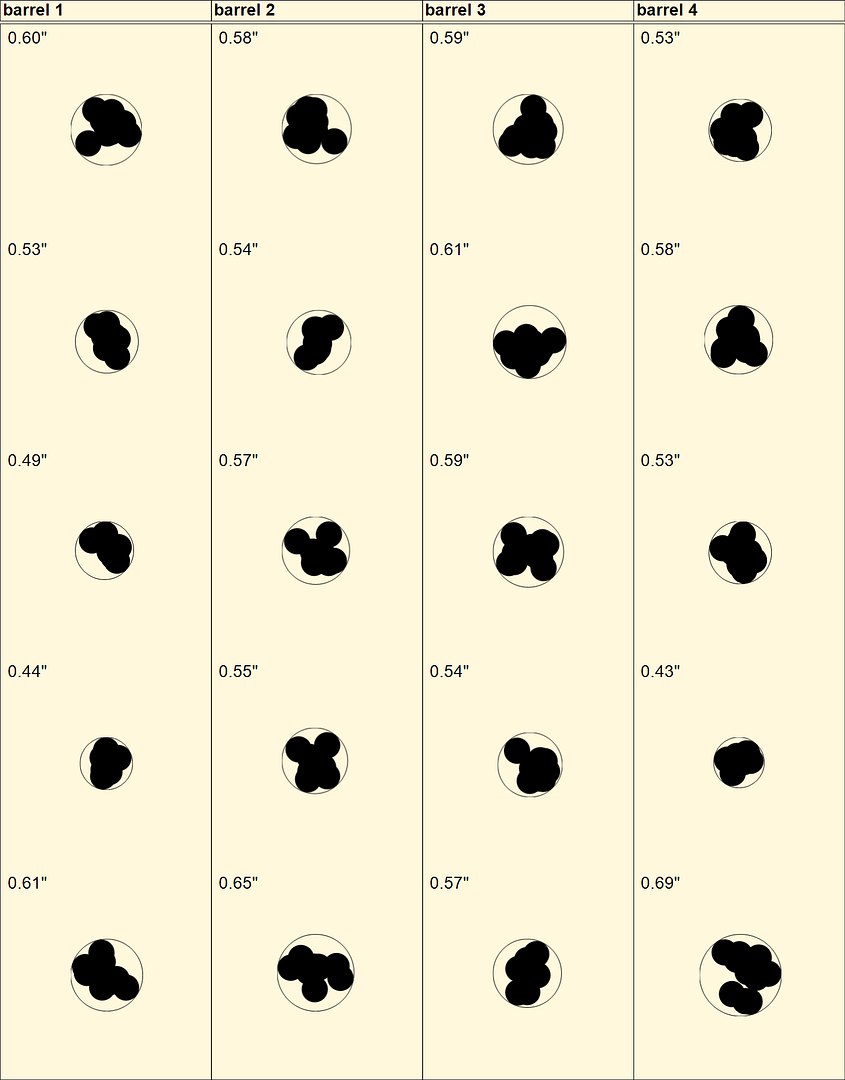

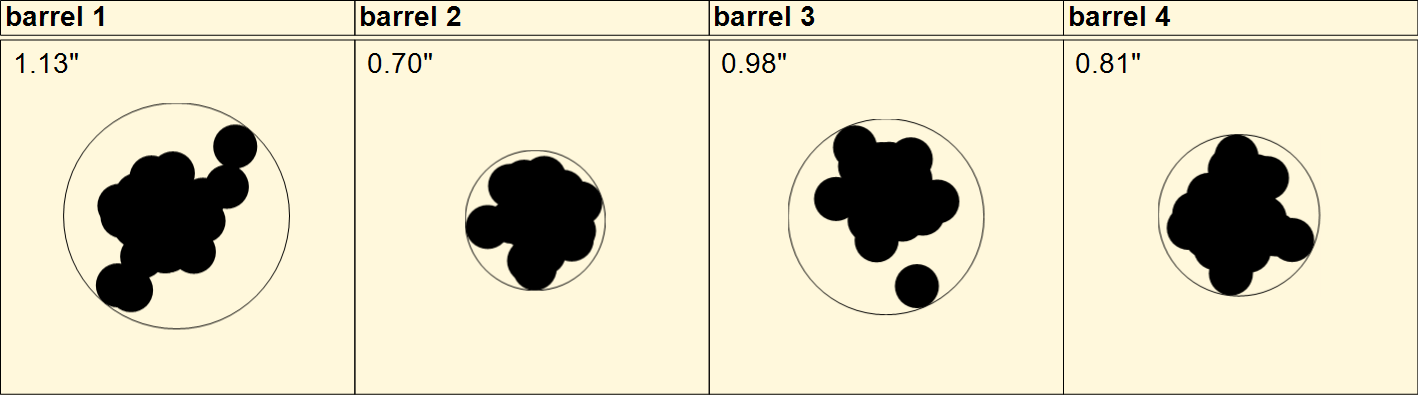

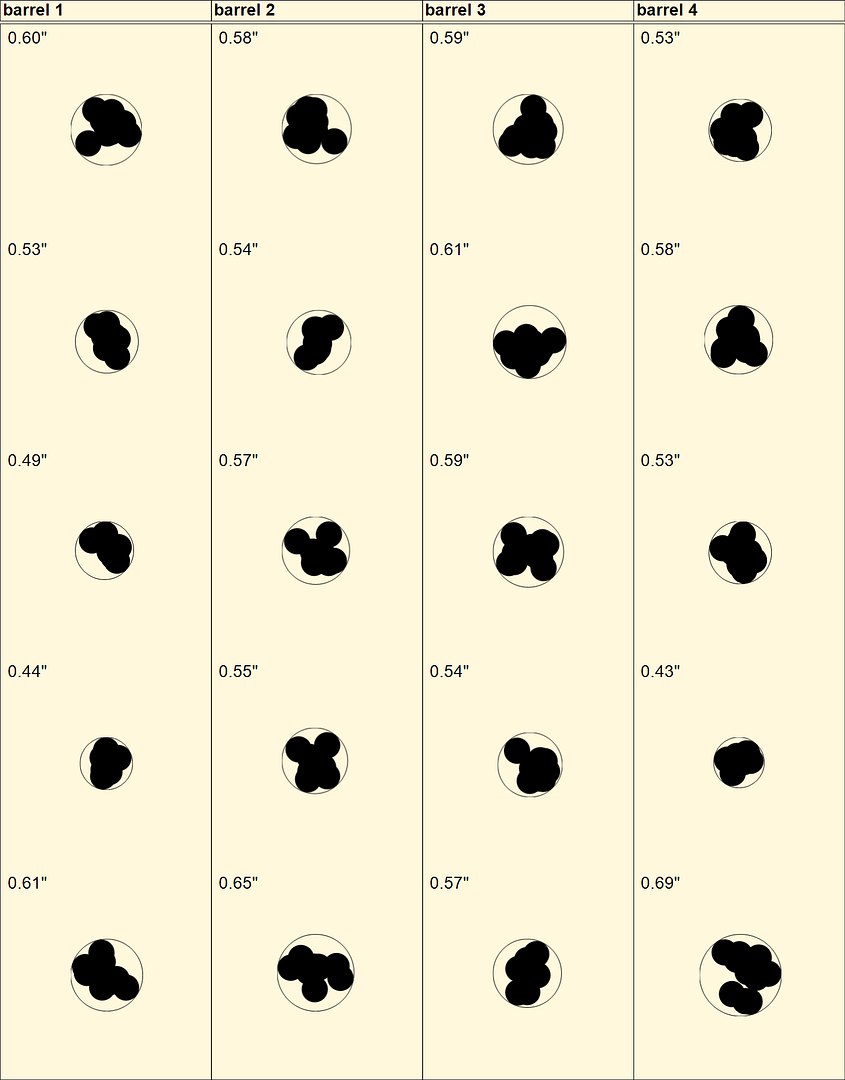

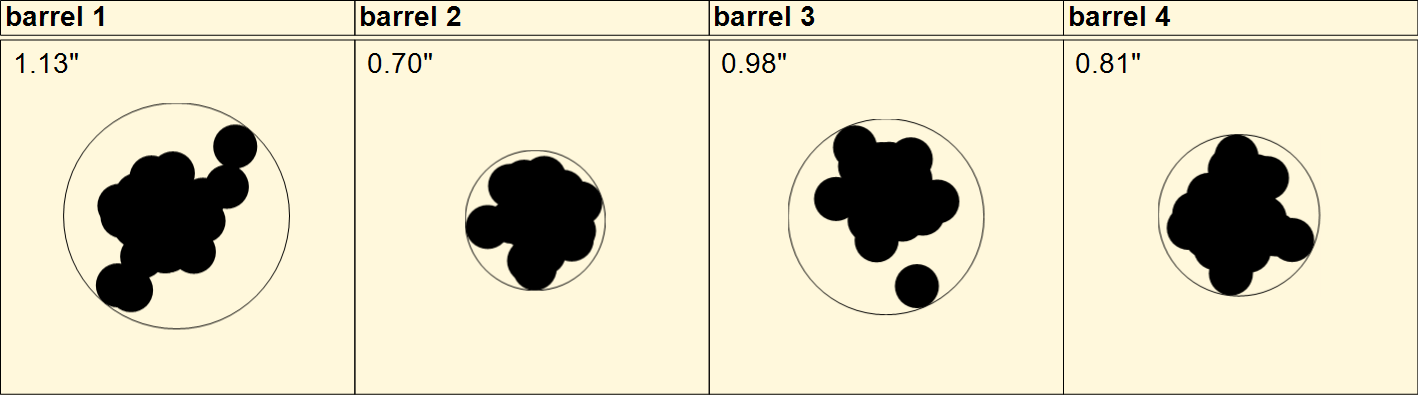

Tenex ammo is Eley's top of the line product. Here's an example of the test results of a good lot of Tenex. It's tested in four different rifles. The first image shows the results at 50 yards, the second an overlap of all shots to show the 50 shot pattern.

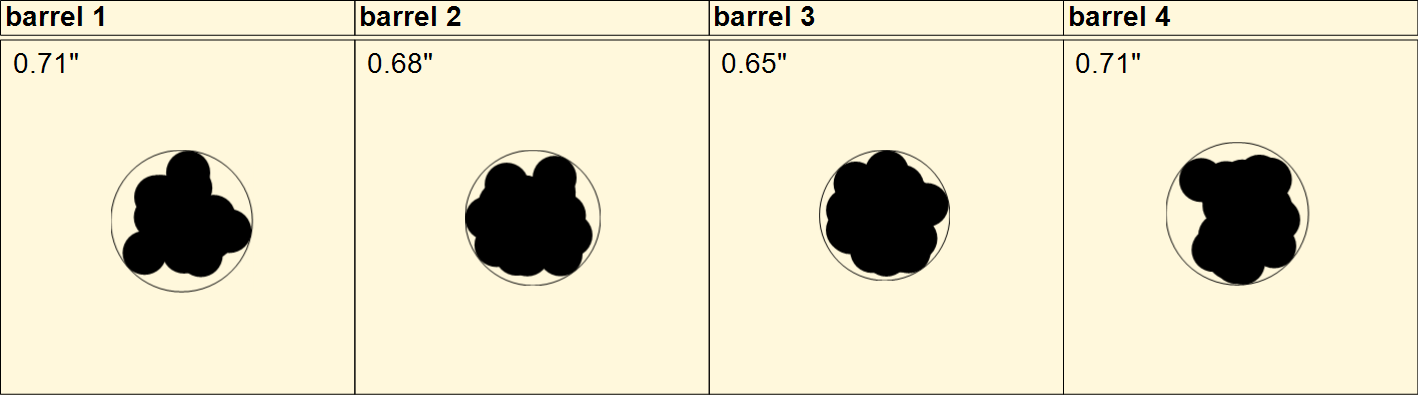

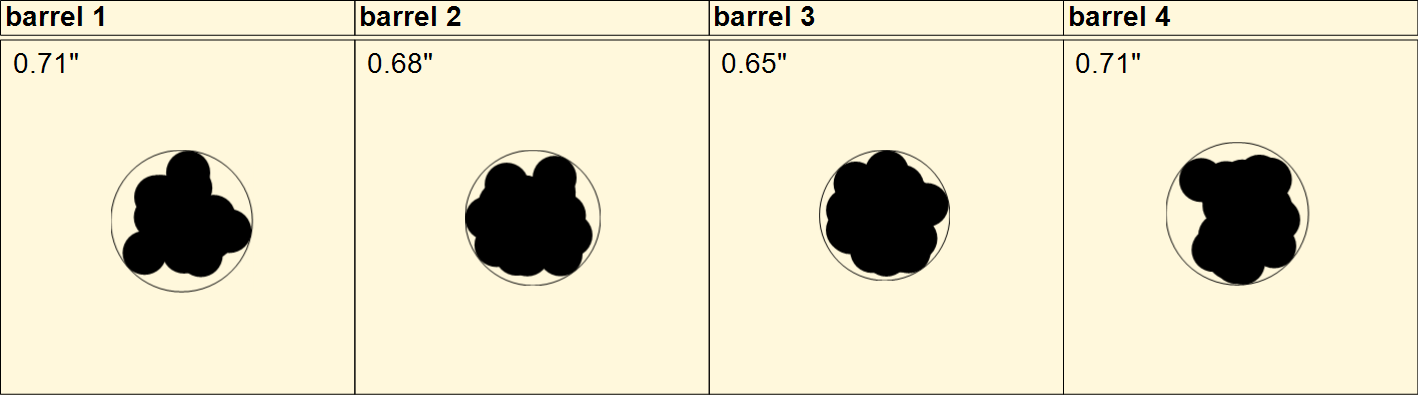

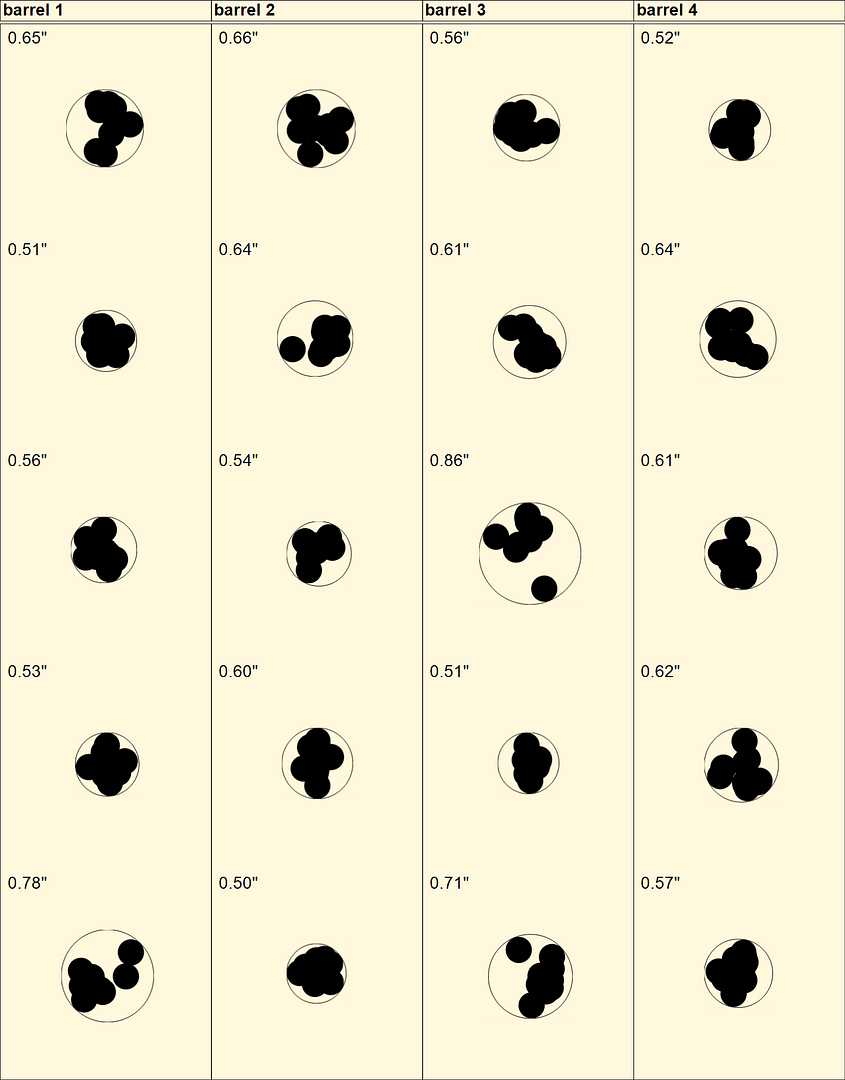

Below are the test results for a different lot of Tenex. The results appear to quite different from those above. The results also show how different barrels can respond to the same ammo.

Other examples can be shown, but the images tell the story. Of course it should be noted that this ammo need not behave this way in any particular rifle, except for those used by Eley for testing.

Continued below.

It will likely require editing and very possibly correction. Any mistakes are mine.

Finding Good Ammo and Why it’s Hard to Find

I continue to learn about shooting .22LR all the time. It’s never ending. Not too long ago I only used .22's casually for hunting and plinking and didn’t give any thought to shooting seriously for accuracy and precision. Now shooting them has become almost an obsession. I shoot from the bench with a front rest and rear bag. I don’t compete. I shoot to try to get the smallest groups possible. I shoot targets of five groups of five shots each or ten groups of five shots. No one else at my range shoots .22LR seriously. Perhaps it’s fortunate that my shooting season is not year round, as my range is accessible only when there is no snow on the ground. There are other things in life besides shooting. More practically I can’t afford to shoot more than a few cases of ammo a year.

Looking back at when I began to learn about shooting .22LR for accuracy and precision – that is, the smallest groups where I wanted them – there are a few things I wish I would have known back then. This is not intended for experienced shooters who have already learned many lessons about .22 rimfire. This is for the neophyte I was not so long ago, some things I know now that I wish I knew back then.

This is about what I learned in general about finding good ammo or understanding why it’s hard to find. It presupposes that the rifle is capable of very good accuracy and precision and that the shooter understands the basics about shooting from the bench. If the rifle is up to the task, getting the most out of it is up to the shooter and the ammo.

It can be a complicated and perplexing mix. Even when assuming consistently good shooting, sometimes a rifle may throw fliers with the best ammo from time to time. But no matter how sound the shooter and rifle might be, the best ammo can’t always be expected to be free of defects or flaws that result in errant shots. It is impossible to avoid altogether. Sometimes rimfire shooting challenges explanation

What have I learned? – A short summary

Often more expensive ammo shoots better than more modestly priced ammo. But it’s not always the case. Ammo quality varies by lot. Most lots are average for that grade of ammo, but some are better and some are worse. The particular lot you have can make a difference between good results and not so good. The same ammo doesn’t necessarily shoot the same with different rifles. Different individual rifles of the same make and model don’t necessarily shoot the same ammo with the same results. The wind can affect results downrange more than many shooters might think.

Finding the best ammo is not easy. When there are errant shots – that is, those that stray from an otherwise good group – they can be caused by one of several things: the wind (if it’s there), the ammo, the rifle, or the shooter or how he sets up his rifle on the bench, a judgment of the shooter nonetheless. The human factor is real especially with shooters who are still learning, working on their technique – but it’s hard to quantify and, I find, harder still to describe.

Finding the ammo your rifle “likes”?

When I began to read about .22 rimfire accuracy, one of the first things I learned was to use standard velocity ammo because it is usually more accurate than high velocity ammo. That was true then and will continue to be true.

I also thought I learned that it was very important to “find the ammo your rifle likes”. By testing a variety of ammos it was supposed to be possible to find the kind that shot most accurately. There is some truth in that kind of advice but there is something misleading in it too. It’s not the same as sampling different flavours of ice cream and picking the one you like. You can say you like chocolate, but not all chocolate ice cream tastes the same.

If testing a number of different ammos, it is possible to identify one of them as producing better results than the others. This is the easy part.

Is it as easy as that? Not really.

It might be tempting to suggest that all that testing should show that the more expensive ammo should produce the best results. That would be a convenient “short cut” and it might happen. The best results, however, might come from ammo other than the most expensive. We simply can’t know in advance. Why? There are several factors at play here and they affect every variety of ammo.

While every rifle may shoot the same ammo differently, perhaps the biggest variable is the ammo itself. Different brands of ammo have unique characteristics. They can have differences in casings, primer material, and propellant – including bullet composition and sometimes shape. Even when it has the same name on it, it doesn’t necessarily shoot the same. To a greater or lesser degree, each variety of ammo has unique characteristics with the result that they respond differently in different rifle barrels. We usually can’t discern these differences by looking at the ammo. The differences, however, are revealed in their own way on the targets.

Lot variation.

Ammo is made in batches called lots. The ammo in each lot should be very similar. But some lots have more consistency between individual boxes or rounds than others. While most lots are generally close to each other in terms of accuracy results, there are differences that can make two different lots of the same ammo seem as different as night and day. A lot of ammo that shoots well in one rifle may not shoot nearly as well in another. That is because each rifle is unique to a degree. Two rifles of the same make and model may not shoot the same lot of ammo with the same results.

To illustrate I’ve shot some lots of Center X that has produced very good results with one of my Anschutz rifles. At the same time I’ve shot other lots of Center X with the very same rifles and the results are consistently inconsistent, so much so that the results are embarrassing in comparison. While most lots of a given brand are relatively close to one another in terms of results, sometimes the differences can be significant.

Is every variety of ammo populated by inconsistent lots? I think there is a good chance that all varieties of ammo have inconsistent shooting lots. I’ve shot some lots of SK Standard Plus and SK Rifle Match that have produced better results than some lots of Center X. I’ve had some lots of Midas Plus shoot very well indeed, while others are poor enough to not justify the cost of $200 per brick (500 rounds). While it is often more accurate, the price tag of the match ammo is not a guarantee that it will shoot well in your particular rifle or even better than less expensive fare.

To illustrate the potential difference between one lot and another -- and, incidentally, to show how different barrels can produce different results with the same ammo -- consider these results from the Eley Lot analyser, which shows, for what they're worth, Eley test results for their various ammo products, according to lot number.

Tenex ammo is Eley's top of the line product. Here's an example of the test results of a good lot of Tenex. It's tested in four different rifles. The first image shows the results at 50 yards, the second an overlap of all shots to show the 50 shot pattern.

Below are the test results for a different lot of Tenex. The results appear to quite different from those above. The results also show how different barrels can respond to the same ammo.

Other examples can be shown, but the images tell the story. Of course it should be noted that this ammo need not behave this way in any particular rifle, except for those used by Eley for testing.

Continued below.