Dark Alley Dan

CGN Ultra frequent flyer

- Location

- Darkest Edmonton

The U-570 had the distinction of being one of the very few naval vessels to surrender to an aircraft.

This from Wikipedia:

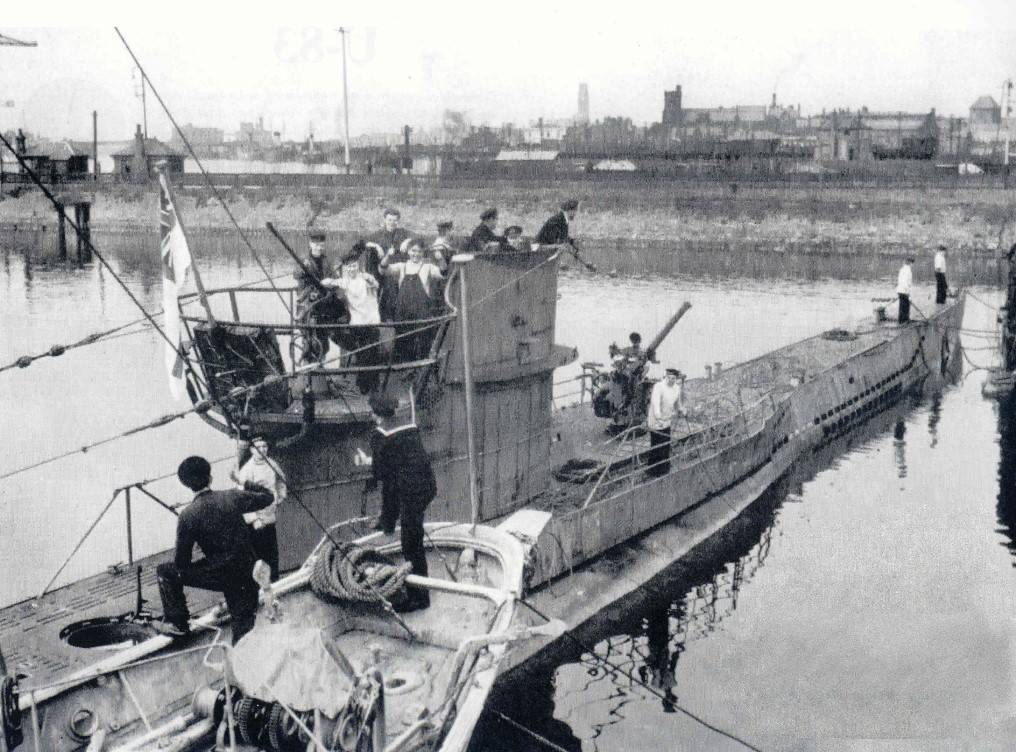

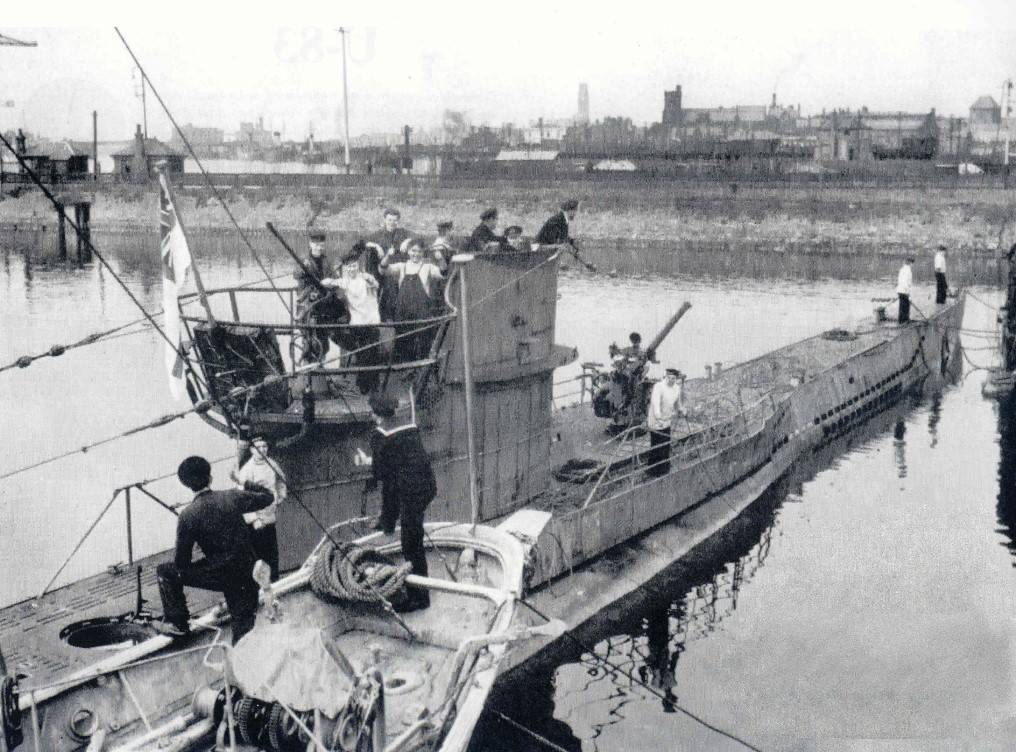

A crew spent time time getting her seaworthy again and she sailed to Barrow-In-Furness on 3 October 1941. Pathe covered her arrival:

[youtube]VJSV8JOhqj4[/youtube]

She spent the next three years serving the RN as HMS Graph.

Finally, with spares unavailable and issues piling up, she was sent to the scrapper. She broke loose of her towline and went aground off the coast of Scotland, where bits of her remain today.

This from Wikipedia:

On 27 August 1941, U-570 spent much of the morning submerged. She had been four days at sea and this was to give respite to a crew that was suffering acutely from seasickness (several had been incapacitated). Earlier that morning, a Lockheed Hudson bomber of 269 Squadron, flown by Sergeant Mitchell and operating from Kaldaðarnes, Iceland, had attacked her. The attack failed when the Hudson's bomb-racks failed to release its depth charges.

U-570 surfaced at position 62°15′N 18°35′W at around 10:50 am, immediately below a second 269 Squadron Hudson, flown by Squadron Leader James Thompson. Thompson was patrolling the area after Mitchell summoned him by radio. Rahmlow, who had climbed out onto the bridge, heard the approaching Hudson's engines and ordered a crash-dive. Thompson's aircraft reached U-570 before she was fully submerged and dropped its four 250-pound depth charges—one detonated just 10 yards (10 m) from the boat.

U-570 quickly resurfaced and around 10 of the crew emerged. The Hudson fired on them with machine guns, but ceased when the U-boat crew displayed a white sheet. The captured crewmembers later recounted to British naval intelligence interrogators what had happened—the depth charge explosions had almost rolled the boat over, knocked out all electrical power, smashed instruments, caused water leaks, and contaminated the air on the boat. The inexperienced crew believed the contamination to be chlorine, caused by acid from leaking battery cells mixing with sea-water, and the engine-compartment crew panicked and fled forward to escape the gas. Restoring electrical power—for the underwater electric motors and for lighting—would have been straightforward, yet there was nobody remaining in the engine compartment to do this. The submarine was dead in the water and in darkness. Rahmlow believed the chlorine would make it fatal to stay submerged so he resurfaced. The sea was too rough for the crew to man their anti-aircraft gun so they displayed a white flag to forestall another, probably fatal, depth charge attack from the Hudson—they were unaware the aircraft had dropped all its depth charges.

Most of the crew remained on the deck of the submarine as Thompson circled above them, his aircraft now joined by a second Hudson that had been en route from Scotland to Iceland and had broken off its journey to lend assistance. A radio request for help saw a Consolidated Catalina flying boat of 209 Squadron being scrambled at Reykjavík; it reached the scene three hours later. The German crew radioed their situation to the German naval high-command, destroyed their radio, smashed their Enigma machine, and dumped its parts overboard along with the boat's secret papers. Admiral Dönitz later noted in his war diary that he ordered U-boats in the area to go to U-570's assistance after receiving this report; U-82 responded, but Allied air patrols prevented U-82 from reaching U-570.

U-570's transmission was in plain language and the British intercepted it. Admiral Percy Noble, commander of Western Approaches Command, immediately ordered several ships to race to the scene. By early afternoon, fuel levels had forced the Hudsons to return to Iceland.[Note 3] The Catalina, a very long-range aircraft, was ordered to watch the submarine until Allied ships arrived. If none came before sunset, the aircraft was to warn U-570's crew to take to the water, then sink her. The first vessel to reach U-570, the anti-submarine trawler HMT Northern Chief, arrived around 10pm, guided to the scene by flares the Catalina dropped. The Catalina returned to Iceland after having circled U-570 for 13 hours.

The German crew remained on board U-570 overnight; they made no attempt to scuttle their boat as Northern Chief had signalled she would open fire and not rescue survivors from the water if they did this (Northern Chief's captain, N.L. Knight, had been ordered to prevent the submarine from being scuttled by any means.) During the night, five more Allied vessels reached the scene: the armed trawler Kingston Agate, two anti-submarine whalers, the Royal Navy destroyer HMS Burwell, and the Canadian destroyer HMCS Niagara.

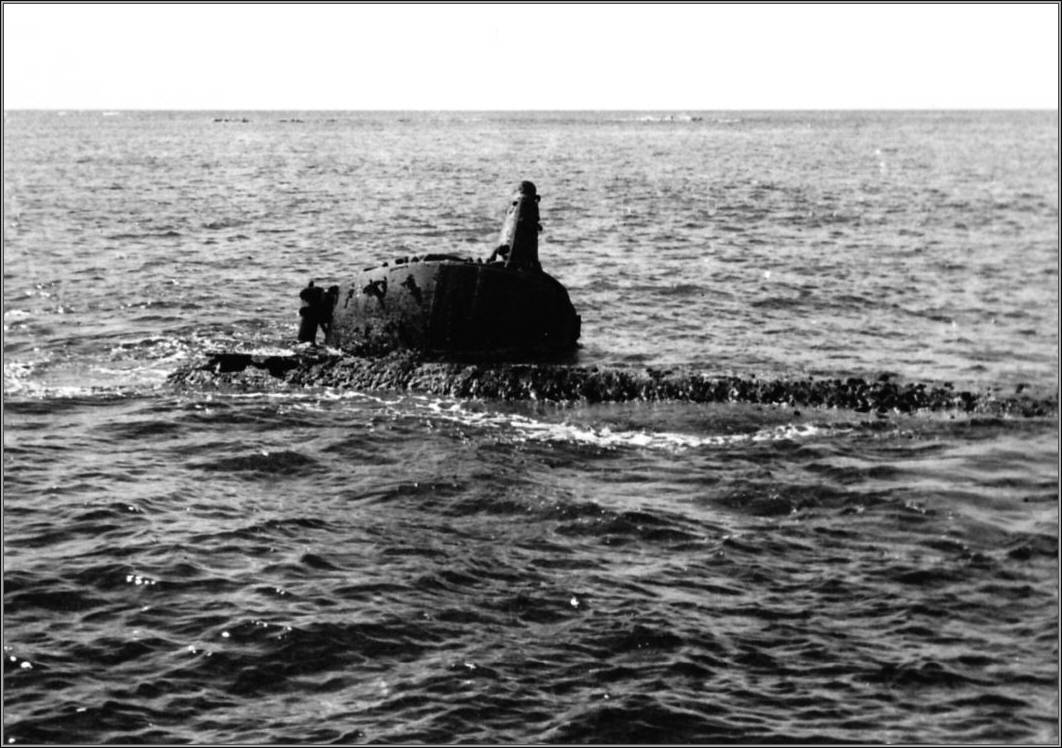

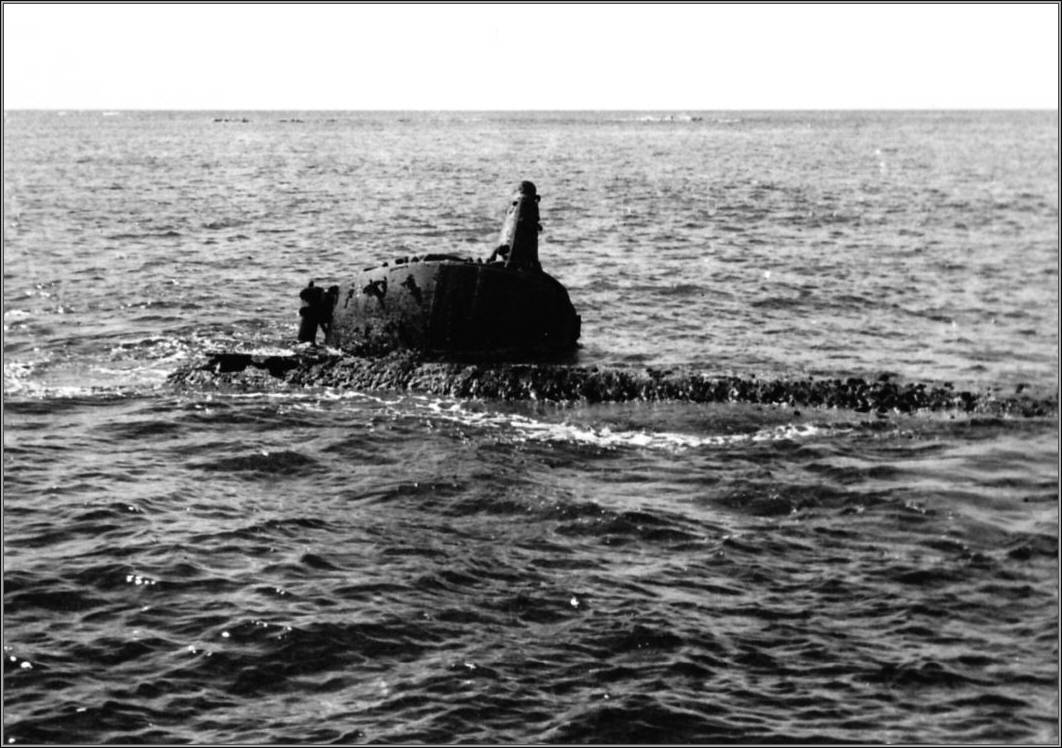

At daybreak, the Allies and Germans exchanged signal lamp messages, with the Germans repeatedly requesting to be taken off as they were unable to stay afloat, and the British refusing to evacuate them until the Germans secured the submarine and stopped it from sinking—the British were concerned that the Germans would deliberately leave behind them a sinking U-boat if they were evacuated. The situation became more confused when a small float-plane, (a Northrop N-3PB of 330 (Norwegian) Squadron), appeared. Unaware of the surrender, it attacked U-570 with small bombs and fired on Northern Chief, which fired back. No damage was done and Burwell ordered the aircraft away by radio.

The weather worsened; several attempts to attach a tow-line to U-570 were unsuccessful. Believing the Germans were being obstructive, Burwell's captain, S.R.J. Woods ordered a machine gunner to fire warning shots, shots that accidentally hit and slightly wounded five of the German crew. With much difficulty, an officer and three sailors from Kingston Agate reached the submarine using a Carley float (a liferaft). After a quick search failed to find the U-boat's Enigma machine, they attached a tow line and carried out the transfer of the five wounded men and the submarine's officers to Kingston Agate. The remaining crew were taken on board HMCS Niagara, which by this time had come alongside U-570.

The ships began slowly sailing to Iceland with U-570 under tow, and with a relay of Hudsons and Catalinas constantly patrolling overhead. They arrived at dawn on 29 August at Þorlákshöfn. There, they beached U-570 as she had been taking on water and was thought to be in danger of sinking.

A crew spent time time getting her seaworthy again and she sailed to Barrow-In-Furness on 3 October 1941. Pathe covered her arrival:

[youtube]VJSV8JOhqj4[/youtube]

She spent the next three years serving the RN as HMS Graph.

Finally, with spares unavailable and issues piling up, she was sent to the scrapper. She broke loose of her towline and went aground off the coast of Scotland, where bits of her remain today.